What is a Marimo?

Marimo is a Japanese word that consists of “ball” (mari; 毬) and “algae” (mo; 藻). It refers to the rare ball form of Aegagropila linnaei, a species of algae that could be found in limited numbers of lakes and seas in the Northern hemisphere. In the wild, Marimo’s spherical shape is gradually formed through A. linnaei’s rotation on sand caused by water flow (Sakai, 1991). Although up to 124 worldwide locations have been reported to be the habitat for Marimo (Boedeker et al, 2010a), Lake Akan in Japan and Lake Mývatn in Iceland are the only two places in which visible quantities still persist (UNESCO, 2011). Yet, collecting Marimo from these two locations is illegal; Lake Akan is a national park while Lake Mývatn is a nature reserve, and both have been included in The Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance. Furthermore, Marimo in Lake Akan has been declared as a National Treasure of Japan since 1921 (Yoshida, n.d.; Guiry, 2013) and it is also a protected species in Iceland since 2006 (Einarsson, 2008).

Marimo in the Aquarium Trade

Most, if not all, Marimo sold in the market today are commercially farmed i.e. being grown vegetatively from fragments. A worldwide survey conducted by Boedeker et al (2010a) has concluded that all Marimo in the aquarium trade originated from Ukraine, and it is the same case for those sold in Japanese aquarium shops. Nonetheless, DNA sequence analyses such as that by Boedeker et al (2010b) have shown that all Marimo are of the same species regardless of their habitats, with Japan being the ancestral area.

Attractiveness of Marimo

Marimo bear a certain likeness to the Earth in being green and round and in their need to rotate to receive light on all sides. In extremely rare occasion, they could develop white exterior (Marimo-web.org, n.d.). Due to their unique appearance, Marimo are popular as gifts. They symbolise eternal happiness, perpetual friendship, and everlasting love by virtue of their slow growth rate and long life span; studies by Acton (1916) and van den Hoek (1963) have indicated that Marimo grow by less than 1cm in diameter each year.

The tale Tragic Love Story of Senato and Manibe written by Aoki (1924) also helps to promote Marimo as a symbol of love. In the story, Senato, the daughter of Ainu tribe leader, secretly fell in love with Manibe of lower social standing. In one of their rendezvous, Manibe accidentally killed Senato’s formal fiancé who had attacked him. Resenting his action, Manibe threw himself into Lake Akan and Senato followed suit; their souls turned into a Marimo which represents fruitful conclusion of their love. Marimo have proven to be a unique and convenient gift item; it is even portrayed as a suitable souvenir from a trip to “Hell” in the anime The World God Only Knows: Tenri-Hen.

The tale Tragic Love Story of Senato and Manibe written by Aoki (1924) also helps to promote Marimo as a symbol of love. In the story, Senato, the daughter of Ainu tribe leader, secretly fell in love with Manibe of lower social standing. In one of their rendezvous, Manibe accidentally killed Senato’s formal fiancé who had attacked him. Resenting his action, Manibe threw himself into Lake Akan and Senato followed suit; their souls turned into a Marimo which represents fruitful conclusion of their love. Marimo have proven to be a unique and convenient gift item; it is even portrayed as a suitable souvenir from a trip to “Hell” in the anime The World God Only Knows: Tenri-Hen.

How to take care of a Marimo?

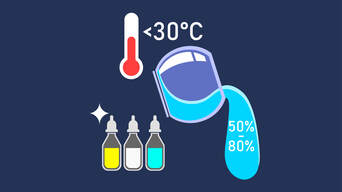

Maintaining a Marimo is an easy task. Its low requirements make it perfect for busy owners. Marimo can thrive in room temperature up to 30 degree Celsius; it requires indirect sunlight or moderate amount of artificial light to carry out photosynthesis, therefore it should not be exposed under direct sunlight for extended period as this will kill the poor little plant.

Marimo requires regular water changes of at least once every fortnight. It is recommended that you change about 50% to 80% of the water (it is recommended that you leave the new water in a container overnight before using it). For Marimo kept in sealed bottles, water changes of at least once a week are needed to replenish the air content. Nonetheless, Marimo is not to be placed under strong running water which might break it apart. In a nutshell, a suitable location and weekly water changes are what it takes to maintain a Marimo!

Common Q&A

1. What is the growth rate and life span of Marimo?

Marimo grow very slowly at around 5 mm in diameter per year. The world largest Marimo is said to be 95 cm in diameter and around 200 years old, although those that exceed 30 cm could easily break the official records (JNTO, n.d.; Marimo.xrea.jp, 2002).

2. Why are there air bubbles around my Marimo?

This is known as pearling and it shows that your Marimo are carrying out photosynthesis.

3. Can I use tap water to keep my Marimo?

Yes, you can use water directly from the tap to keep your Marimo. Unlike fishes, Marimo will not die because of chlorinated water.

4. Do I need to feed my Marimo?

No. Marimo create their food through photosynthesis.

5. Can I keep fishes with Marimo.

Yes. It is recommended that Marimo be kept together with small fishes and shrimps. The former would gobble any annoying mosquito larvae while the latter could help to clean any debris of food used to feed the fishes. Marimo would also act as a natural water filter that removes ammonia which is harmful to fishes. However, beware that your Marimo might end up as perfect greens for some species of fishes (e.g. goldfish).

6. Why is my Marimo floating?

A Marimo might float due to a large amount of air bubbles trapped inside it. This often occurs after water changes. It will sink over time by itself or you could help by gently squeezing it underwater.

7. Why is my Marimo growing unevenly?

During growth, Marimo in aquarium might develop uneven parts. In the wild, Marimo keeps its ball shape thanks to constant water flow, but there is no such flow that keeps it round in your container. You could gently rub your Marimo to maintain its ball shape if you feel like to do so.

8. Will Marimo get sick?

Yes. Marimo will get sick and even die if not given proper care. Remember to change their water weekly and avoid extended exposure under direct sunlight or extreme temperature. Sick Marimo will turn brown in colour. Copy from Marimo Malaysia

9. Can I keep my Marimo inside a sealed bottle?

Yes. This could prevent mosquitos from laying eggs in the water. However, frequent water changes must be carried out to provide the Marimo with fresh water and air.Copy from Marimo Malaysia

10. Will Marimo cause algae boom in my tank?

No. Rest assure that Marimo are not known to lead to any alga problem.

Bibliography

Acton, E. (1916). “On the structure and origin of “Cladophora balls.”” New Phytologist, Vol. 15, pp. 1-10.

Aoki, J. (1924). Legends and Love Stories of Ainu. Sapporo: Fukido Shobo.

Boedeker, Christian; Eggert, Anja; Immers, Anne; and Smets, Erik. (2010a). “Global Decline of and Threats to Aegagropila linnaei, with Special Reference to the Lake Ball Habit.” BioScience, Vol. 60(3), pp. 187-198.

Boedeker, Christian; Eggert, Anja; Immers, Anne; and Wakana, Isamu. (2010b). “Biogeography of Aegagropila linnaei (Cladophorophyceae, Chlorophyta): a widespread freshwater alga with low effective dispersal potential shows a glacial imprint in its distribution.” Journal of Biogeography, Vol. 37, pp. 1491-1503.

Einarsson, Arni. (2008). “Marimo lake balls in Mývatn.” Nattura.info. Retrieved from nattura.info/2008/09/22/marimo-lake-balls-in-myvatn as at 19th October 2013.

Guiry, M. D. in Guiry, M. D. and Guiry, G. M. (2013). “Aegagropila linnaei Kützing.” AlgaeBase. World-wide electronic publication, National University of Ireland. Retrieved from www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=59094 as at 19th October 2013.

Author: Neoh Jia En (Okeanos E-aquarium)

JNTO (Japan National Tourism Organization). (n.d.). "Marimo Matsuri." Retrieved from www.jnto.go.jp/eng/location/spot/festival/marimo.html as at 19th October 2013.

Marimo-web.org. (n.d.). “Marimo in Japan; Marimo Worldwide.” Retrieved from www.marimo-web.org/japan_world.html (website in Japanese) as at 19th October 2013.

Marimo.xrea.jp. (2002). "Year-End Plan." Retrieved from marimo.xrea.jp/corner/marimo2002.html (website in Japanese) as at 19th October 2013.

Sakai, Y. (1991). Science of Aegagropilas. Sapporo: Hokkaido University Press.

UNESCO. (2011). “Mývatn and Laxá.” Retrieved from whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5586/ as at 19th October 2013.

van de Hoek, C. (1963). Revision of the European Species of Cladophora. E. J. Brill.

Yoshida, Tadao. (n.d.). “Marimo.” Japan Integrated Biodiversity Information System. Retrieved from www.biodic.go.jp/cgi-db/gen/rdb_g2000_sy2.RDB_DETAIL?code=B0015&rank=&search_str=%a5%de%a5%ea%a5%e2&start_row=1&gaku_n=&bunrui=% (website in Japanese) as at 19th October 2013.

Aoki, J. (1924). Legends and Love Stories of Ainu. Sapporo: Fukido Shobo.

Boedeker, Christian; Eggert, Anja; Immers, Anne; and Smets, Erik. (2010a). “Global Decline of and Threats to Aegagropila linnaei, with Special Reference to the Lake Ball Habit.” BioScience, Vol. 60(3), pp. 187-198.

Boedeker, Christian; Eggert, Anja; Immers, Anne; and Wakana, Isamu. (2010b). “Biogeography of Aegagropila linnaei (Cladophorophyceae, Chlorophyta): a widespread freshwater alga with low effective dispersal potential shows a glacial imprint in its distribution.” Journal of Biogeography, Vol. 37, pp. 1491-1503.

Einarsson, Arni. (2008). “Marimo lake balls in Mývatn.” Nattura.info. Retrieved from nattura.info/2008/09/22/marimo-lake-balls-in-myvatn as at 19th October 2013.

Guiry, M. D. in Guiry, M. D. and Guiry, G. M. (2013). “Aegagropila linnaei Kützing.” AlgaeBase. World-wide electronic publication, National University of Ireland. Retrieved from www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=59094 as at 19th October 2013.

Author: Neoh Jia En (Okeanos E-aquarium)

JNTO (Japan National Tourism Organization). (n.d.). "Marimo Matsuri." Retrieved from www.jnto.go.jp/eng/location/spot/festival/marimo.html as at 19th October 2013.

Marimo-web.org. (n.d.). “Marimo in Japan; Marimo Worldwide.” Retrieved from www.marimo-web.org/japan_world.html (website in Japanese) as at 19th October 2013.

Marimo.xrea.jp. (2002). "Year-End Plan." Retrieved from marimo.xrea.jp/corner/marimo2002.html (website in Japanese) as at 19th October 2013.

Sakai, Y. (1991). Science of Aegagropilas. Sapporo: Hokkaido University Press.

UNESCO. (2011). “Mývatn and Laxá.” Retrieved from whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5586/ as at 19th October 2013.

van de Hoek, C. (1963). Revision of the European Species of Cladophora. E. J. Brill.

Yoshida, Tadao. (n.d.). “Marimo.” Japan Integrated Biodiversity Information System. Retrieved from www.biodic.go.jp/cgi-db/gen/rdb_g2000_sy2.RDB_DETAIL?code=B0015&rank=&search_str=%a5%de%a5%ea%a5%e2&start_row=1&gaku_n=&bunrui=% (website in Japanese) as at 19th October 2013.